My last post generated some strong reactions. Thanks to those of you who took the time to provide constructive feedback and keep the conversation going. Many of you told me that our unity in the UMC is not simply located in our polity but in Jesus Christ. Jesus is what unites us.

I want to believe this is true, but the theological pluralism embedded in the “Theological Task” section of the 1972 Discipline has had long-lasting and far-reaching effects. Nevertheless, for the sake of conversation, Iet’s drill a bit deeper into what it might mean to be united in Christ.

It’s safe to say that virtually all people who call themselves Christian regard Jesus as in some way important. But why is he important? To put things in fairly broad categories, Christians have claimed that Jesus is important because of (a) who he is (b) what he has done, and (c) what he will do.

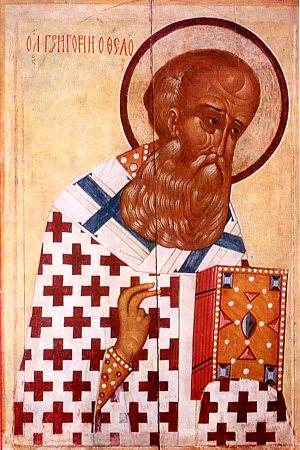

Most Christians, following the Roman Catholic and Orthodox traditions of the Church, have affirmed that Jesus was the incarnate Second Person of the Trinity. This statement of who Jesus is cannot be separated from what he has done and what he will do. Jesus has atoned for our sins, made it possible for us to be reconciled to God, and will come again in judgment. His incarnation is essential for our salvation because, as Gregory of Nazianzus put it, “that which he has not assumed, he has not healed.” Put differently, for God to heal the sinful and broken nature of humankind, it was necessary for God to take on the nature of humankind. Only in Christ could the perfection of God and the brokenness of humanity be united. Athanasius put the matter positively: Christ became human that we might become “gods.” In other words, in the divine-human union, all humankind was given the opportunity to be transformed into the likeness of Christ and live forever in harmony with the Triune God.

Most Christians, following the Roman Catholic and Orthodox traditions of the Church, have affirmed that Jesus was the incarnate Second Person of the Trinity. This statement of who Jesus is cannot be separated from what he has done and what he will do. Jesus has atoned for our sins, made it possible for us to be reconciled to God, and will come again in judgment. His incarnation is essential for our salvation because, as Gregory of Nazianzus put it, “that which he has not assumed, he has not healed.” Put differently, for God to heal the sinful and broken nature of humankind, it was necessary for God to take on the nature of humankind. Only in Christ could the perfection of God and the brokenness of humanity be united. Athanasius put the matter positively: Christ became human that we might become “gods.” In other words, in the divine-human union, all humankind was given the opportunity to be transformed into the likeness of Christ and live forever in harmony with the Triune God.

Doctrine is a delicate matter. It is rather like a game of Jenga. As you begin to remove pieces of the structure, it becomes ever less stable. One piece relies on another piece, and with the removal of just a few key ideas, the entire system becomes incoherent. In other words, the structure tumbles.

Photo by Guma89, courtesy Wikimedia Commons athttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jenga_distorted.jpg

To help stabilize the structure of our affirmations about God’s saving work in Jesus Christ, the Church developed creeds, the two most important of which are the Nicene Creed and the Apostles’ Creed. Consider the second article of the Nicene Creed:

We believe in one Lord Jesus Christ,

the Only Begotten Son of God,

born of the Father before all ages.

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father;

through him all things were made.

For us men and for our salvation

he came down from heaven,

and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary,

and became man.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate,

he suffered death and was buried,

and rose again on the third day

in accordance with the Scriptures.

He ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory

to judge the living and the dead

and his kingdom will have no end.

A more basic Christological summary can be found in the Apostles’ Creed. Jesus Christ is:

[the] only Son [of the Father], Our Lord,

Who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried.

He descended into Hell; the third day He rose again from the dead;

He ascended into Heaven, and sitteth at the right hand of God, the Father almighty; from thence He shall come to judge the living and the dead.

Okay… maybe we can leave out the “descended into hell” part…. This affirmation has a complex history and has found its way in and out of the Apostles’ Creed many times, depending upon the community of faith in which the creed was recited.

But we all affirm the other parts, right?

[*Crickets]

I mean, after all, the affirmations of these creeds are presupposed in the Articles of Religion, one of our doctrinal standards within The United Methodist Church. Consider Articles II and III:

Article II – Of the Word, or Son of God, Who Was Made Very Man

The Son, who is the Word of the Father, the very and eternal God, of one substance with the Father, took man’s nature in the womb of the blessed Virgin; so that two whole and perfect natures, that is to say, the Godhead and Manhood, were joined together in one person, never to be divided; whereof is one Christ, very God and very Man, who truly suffered, was crucified, dead, and buried, to reconcile his Father to us, and to be a sacrifice, not only for original guilt, but also for actual sins of men.

Article III – Of the Resurrection of Christ

Christ did truly rise again from the dead, and took again his body, with all things appertaining to the perfection of man’s nature, wherewith he ascended into heaven, and there sitteth until he return to judge all men at the last day.

And we must not forget about the affirmations of that oft-neglected part of our United Methodist tradition, the Evangelical United Brethren, which gave us the Confession of Faith:

Article II – Jesus Christ

We believe in Jesus Christ, truly God and truly man, in whom the divine and human natures are perfectly and inseparably united. He is the eternal Word made flesh, the only begotten Son of the Father, born of the Virgin Mary by the power of the Holy Spirit. As ministering Servant he lived, suffered and died on the cross. He was buried, rose from the dead and ascended into heaven to be with the Father, from whence he shall return. He is eternal Savior and Mediator, who intercedes for us, and by him all men will be judged.

It comes down to which Jesus? The one of Scripture and the Great Tradition as expressed in the Creed, or the Jesus of our own making.

Pete, I agree with this (as I’m sure you already know).

Pingback: Unity in Christ (?) | David F. Watson | John Meunier

Isn’t the real question: Is dissent acceptable, regardless of how any given majority collectively identifies who Christ is?

Britt, isn’t the real question: I want to be free to determine and define for myself who I want Christ to be, and to not be beholden or accountable to any standard outside of myself?

I think the formulation is unfair. The proposition is not: “I want to be free to determine and define for myself who I want Christ to be”. It is: “I want to be free to use my own mind to make my own determination based on the best evidence available to me about who the historical Jesus was. I do not want to be beholden to a standard that is first and last based on the opinion of other people in current and previous ages 1) whose motives I cannot be clear about 2) who may or not have had clear evidence for their beliefs 3) who may have believed many things based on the provincial standard or their times.” Freedom to think for one’s self based on one’s one evaluation of evidence and one’s own conscience was one of the key themes in our founding as a nation. I think it fits it’s still a pretty good theme.

Evan, I assert that we ALL determine and define for ourselves who we want Christ to be, and that those who claim otherwise are only fooling themselves. How do I know that the color blue I see is exactly the same or even similar to the color blue you see?

Britt, that is a valid question, but it is not the question I am asking.

Indeed we reap what we sow…

Dissent, it happens all the time. Everyone is free to think and choose for themselves. I do not think that is the “real question”. At lest it has not been a question in my experience. I see people regularly and freely choosing to dissent, especially in my denomination. A more real question is does the church believe Jesus Christ has a definable identity, and second, if yes, how does one derive such a conclusion about that identity?